Image: surveyor holding paper and looking over river.

The Government’s 25-year Environment Plan has, as one of its objectives, “to leave the environment in a better state than we found it.”

As expressed in the Environment Act, starting in 2024, developers will need to ensure at least a 10% net gain in biodiversity on their development land. Achieving that gain may involve creating or enhancing habitats on the development site. If that’s not feasible, the developers might still try and reach that mark via what are termed “off-site” solutions.

The 3 Options in BNG

How net gain will be achieved must be spelled out by developers as part of their planning applications. They must demonstrate how net gain will be achieved in three major aspects:

1) on-site, if feasible;

2) in close proximity to the development; and

3) if not possible in the scenarios above, in new projects somewhere else and with someone else.

BNG Planning Strategy

To do so—and to earn the permission for buildings and other infrastructure to be erected and not harm the environment—the planning and strategy teams of developers must treat the opportunity as a complex business problem. This is not a simple tick-box exercise. To do it well requires problem-solving skills for the development of new types of opportunities that contribute to a sustainable economy.

Biodiversity Units

The biodiversity net gain (BNG) that developers and landowners will create is denoted by “biodiversity units” calculated via the Statutory Biodiversity Metric. This provides a common standard and quality assurance for purchasers and regulates exactly what the provider is required to do. It is interesting to see how BNG interacts with other environmental schemes like ELMS. Benefits can “stack” as long as the same outcomes aren’t double-counted. The British Standards Institution’s guidance, BS 8683, defines this as paying only for something that wouldn’t happen anyway. DEFRA’s definition is somewhat less illuminating: they don’t pay for the same thing twice.

The latter statement indicates greater flexibility and that the by-products of one scheme can be sold separately from its main action (e.g. creating woodland for biodiversity and then selling the carbon that is taken up as credits). In this instance, you are not selling carbon itself twice over because you are being paid to create/improve habitat and not just to sequester carbon, and you’re making use of all the revenue streams available from taking land out of production. It would make sense to structure it this way because it would encourage overall participation by landowners.

The two chief alternatives are (1) the creation of new habitats and (2) the enhancement and restoration of existing habitats. These require the sorts of actions that might be recommended in a Conservation Plan. Such actions include the planting of woodlands, the sowing of wildflower meadows, the creation of wetlands and ponds, the installation of hedgerows, and the establishment of tree lines, scrub belts, and grassland verges.

The Environment Act also requires the establishment of Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS), as England works toward the ambitious goal of achieving net gain for biodiversity. Local Nature Recovery Strategies will be an important tool in local authorities’ delivery of that goal. They will help local authorities pinpoint areas in their jurisdiction that are ripe for nature recovery, but that’s not all they will do. There is some important “how to” guidance in the LNRS provisions in the Environment Act. And they are worth unpacking in some detail.

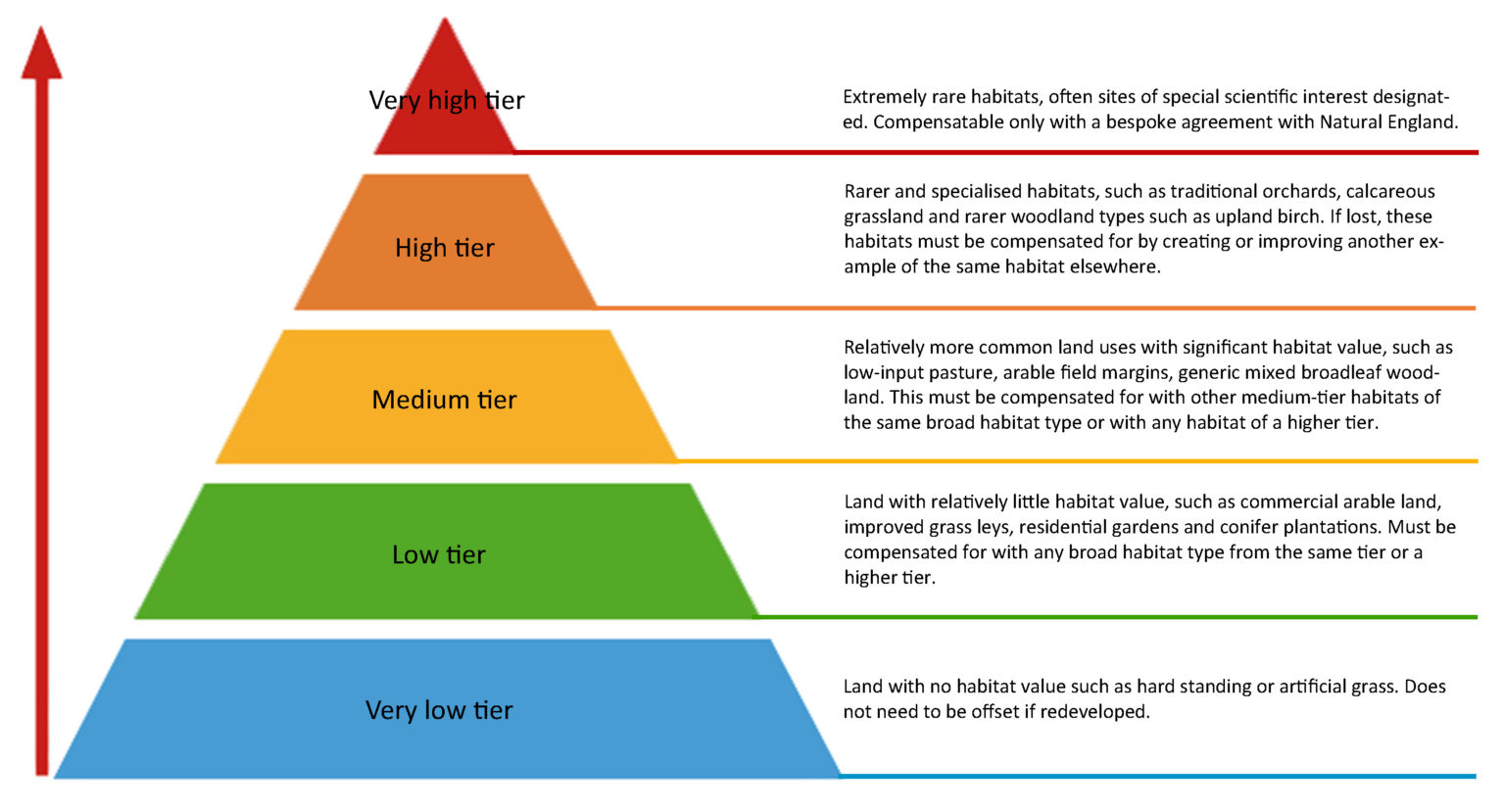

TCS Habitat Distinctiveness/”Rarity” Pyramid

TCS Habitat Distinctiveness/”Rarity” Trading Pyramid

How to calculate a site’s biodiversity units

Calculating original site baseline

In calculating how many units a site will lose or gain, several factors and multipliers are involved, including site area, distinctiveness, condition, strategic significance, impact of development, time to attain the desired level, establishment difficulty, risk, and proximity to the development site.

For a site with very high biodiversity, the units lost from the site and required from off-site projects to make up a 10% net gain will be substantial. This process will tend to discourage new development of any kind on sites with very high biodiversity.

Initially, the baseline situation of the area targeted for development is determined. Next, the developmental actions themselves and any lost pre-existing habitat are factored in and subtracted from this baseline to assess the total impact of the development. Once the developer knows the effect of the development on the area, they have to show that they can make improvements to reach something approaching a net gain. If they don’t show a net gain of 10%, they have to find some off-site solutions to make up the difference.

Calculating units for offsite enhancement

Establish offsite baseline

The area, in hectares or kilometers, for rivers or hedgerows is calculated. There is no minimum or maximum size that is specified, but going under a certain limit would simply be uneconomical. Local authorities are in the process of identifying areas of strategic significance, and if the location of a site is within one of those areas, it receives a 15% increase in the number of units that can be generated. If the site is in a desirable location, but not within an officially identified area of strategic significance, it might receive a 10% increase, provided the Local Authority signs off on it.

Each habitat receives a distinctiveness score ranging from 0 to 8. The rarer it is, the higher the score. This score takes into account not just the habitat but also its surroundings, how much of it there is within SSSIs, and whether it’s considered a UK Priority habitat. They multiply that score by the area.

Then they take the existing habitat condition—from Poor at x1 to Good at x3—and multiply that by their previous score to get the available units. Some habitats automatically get a poor score because they’re so altered (like cereal fields), while others might be better suited to this calculation (like heathland).

As an example, 2 ha of arable would generate:

2 (Area) x 2 (‘Low’ Distinctiveness) x 1 (Condition) x 1 (‘Low’ Strategic Significance) = 4 Units

Account for existing habitat loss

There will already be some habitat value at a site, and the impact of this must be taken into account when calculating the enhancement. To do this, we must arrive at a figure that represents the area with some habitat before any enhancement occurs. This challenge is made more elusive by the first assumption stated above—that we have positive outcomes with every enhancement.

Account for gain of enhanced habitat

The habitat value that has been created or enhanced must be calculated, just as was done for the baseline, but this time using the new scores from the newly configured type of habitat or condition and applying the following relevant multipliers:

Spatial risk – The distance of the new site from the developer’s site will reduce the number of usable units by 25% if the new site is in a nearby Local Authority area and by 50% if the new site is located further away.

Difficulty of creation and time – The time it takes for enhancement or creation of a habitat to reach its desired potential will greatly affect units with reductions of up to 70% if it takes 30 years or longer. The harder it is to do these creations and enhancements, the greater the reduction – up to 10% – in their potential value.

Example – If the above arable site was used to create Gorse Scrub:

2 (Area) x 4 (‘Medium’ Distinctiveness) x 3 (‘Good’ Condition) = 24

x 1 (‘Low’ Strategic Significance) = 24

x 0.7 (Remoteness: 10+ years to establishment) x 1 (‘Low’ Difficulty of creation)

x 1 (Spatial Risk: Within same LPA)

= 16.81 Units minus 4 (Baseline Units Lost)

Net Units = 12.81

The advantages of improving current land rather than making new habitat are worth stating. We may produce more units of habitat via improvement even if what we have is a ‘common’ sort of habitat, in contrast to a newly made ‘rare’ one. This is because sometimes, the enhancement-to-habitat-gain ratio is better than the new-habitat-gain ratio, and this is doubly true when we consider the real-time implications for species that need the habitat.

Whether enhancing or creating habitat, land managers must give careful thought to what sort of habitat they are providing. Factors like establishment time can have a huge effect on unit production; it is as if success depends more on what is not allowed to happen than on what is actually done to manage the area. The opportunity costs of taking land out of production must be offset by the kind of money that can be made from selling BNG units. And don’t forget the growing role of “natural capital” in offsetting our ecological footprint. That’s a whole other essay.

Land developers and credit purchasers

Prior to development work commencing but succeeding the granting of planning permission, one must submit to a planning authority an approved biodiversity gain plan. This plan must show two things at a minimum. First, it must show that the net gain target will be achieved. Second, it must show not how “gain” is going to happen but rather how the value of “gain” has been calculated. In tandem with the above, this plan (or rather the absence of it) is not made necessary if development rights orders (or permission) have at any point been granted.

The ‘net gain’ will be computed by assessing the pre-development biodiversity value (obtained at the planning application submission stage) and subtracting it from the post-development biodiversity value (which will attempt to realize on-site habitat improvements, where feasible). The post-development value may encompass biodiversity that is only realized years down the line, assuming the project proved to be a long-term one.

The value of biodiversity can incorporate off-site possibilities like buying ‘habitat units’ from a site on Natural England’s ‘biodiversity gain register.’

Contact us to obtain appropriate land that meets your offsetting requirements.

Land owners and vendors

Should you wish to have a biodiversity report prepared that will establish your land’s baseline value as well as suitable habitat interventions necessary to yield net units, then contact us for our welcome pack. This welcome pack explains everything you need to know and provide to enable us to quote for carrying out a site survey and site assessment.

Should you have land prepared for the “biodiversity gain register,” having completed your Metric reports, then get in touch with us to talk about your alternatives and assist you with the unit sale stage. You would need to register and work out:

- The size and location of the land;

- What habitat enhancement works will be carried out, and what are the specific benefits;

- Information about the land’s habitat prior to commencement of enhancements;

- Identity of the person who applied to register the land, and (if different) the person by whom the requirement to carry out the works or maintain habitat enhancement is enforceable;

- Any development to which part of the habitat enhancement has been allocated;

- The biodiversity value by using the Statutory Biodiversity Metric tool.

Image: surveyor making calculations on iPad.

How to calculate biodiversity value

DEFRA initially laid out an outline tariff of £9,000 to £12,000 per biodiversity unit. More recent consultations have suggested a possible range of £20,000 to £25,000 per unit. The idea is to make the scheme attractive to potential sellers by determining not to use models based on compensatory payments or income-forgone calculations.

Of course, the actual payments will depend on specific circumstances. A prime candidate for high-end payments would be converting each hectare of arable land to neutral grassland capable of producing around 6.4 units/ha—a conversion that would likely be required to do so on-site and meet the necessary conditions for this type of habitat. Payments could amount to a total £128,000 or around £4,265 per hectare per annum for 30 years.

Transforming one hectare of altered grassland into lowland meadow could deliver a net 8.64 units under optimal conditions (distance, within formally identified area, etc.). This would equate to approximately £172,800 or nearly £5,760 per hectare per year for 30 years, assuming we could sell all the units and that they would fetch the kinds of prices specified above. Take note, though: actually getting any money in hand is contingent on the not always speedy process of completing sales. Whether we could sell all the units depends on supply and demand.

What can we do to help?

Register your interest now with us to take advantage of Biodiversity Net Gain schemes as they develop. Our team can help by:

- Advising on the suitability of any area of land for Biodiversity Net Gain;

- Calculating potential Biodiversity Units using DEFRA’s Statutory Biodiversity metric;

- Adding you to our register and matching you with conveniently located land that meets your Biodiversity Units goals;

- Valuing land for investment purposes, considering a wide range of environmental credits and ‘nature capital’, ideal for woodland creation for carbon units to habitat improvement for BNG.

For our Biodiversity Net Gain user guide, email us for our welcome pack.